BONUS NUMBER 102: JUDY GARLAND, JEANETTE MacDONALD, SUSAN KOHNER, AND THE GRANDDADDY OF GRINDR AND SQUIRT

(Did You Sleep With the Models?)

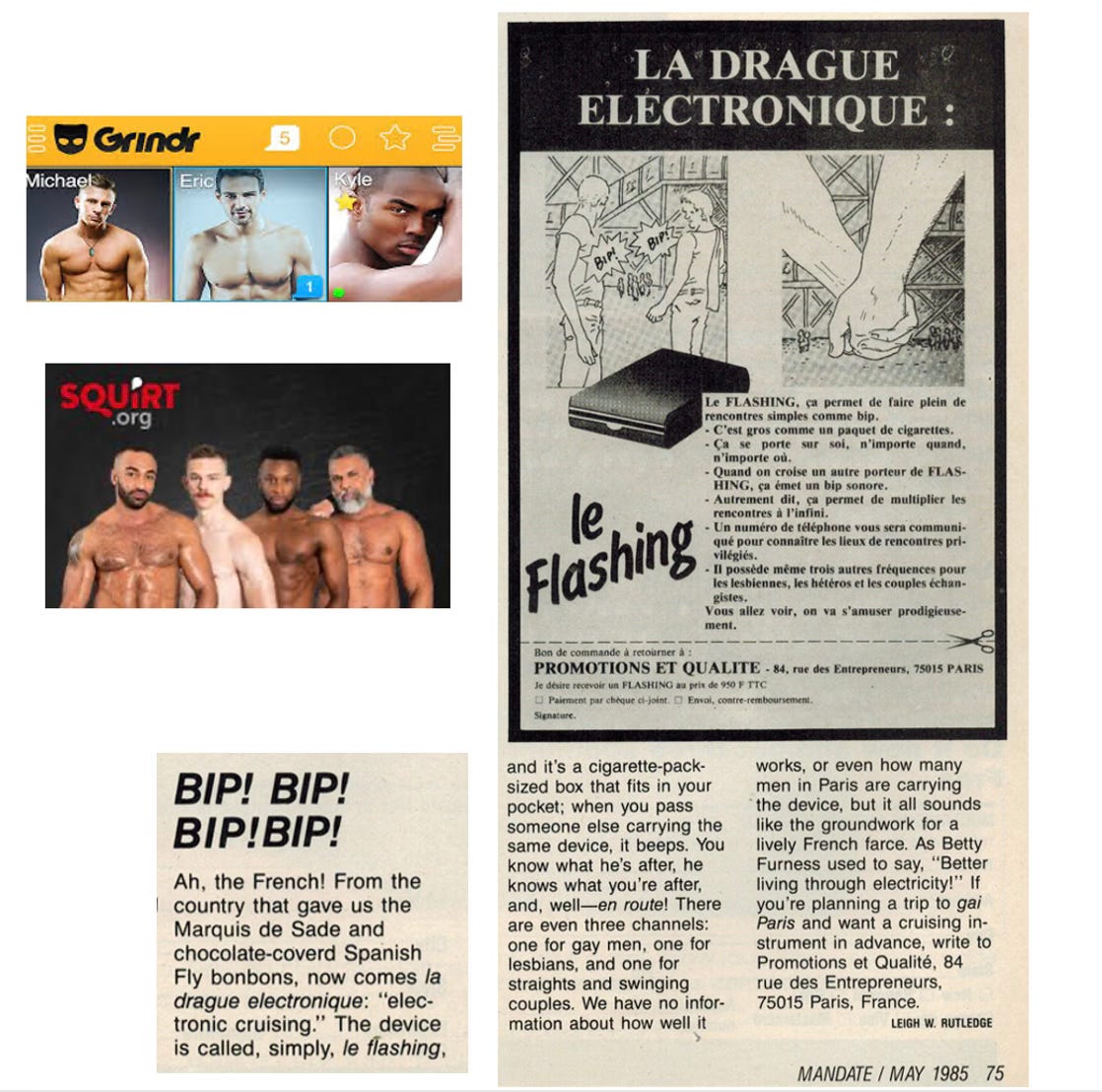

“Mandata” was the title of Mandate’s monthly catch-all column. My associate editors and I were always on the lookout for newsy tidbits, outlandish events involving gays, entertainment and political goings-on, and unusual products such as “la drague electronique,” which I’ve dubbed here the granddaddy of Grindr and Squirt. It was frequent contributor Leigh W. Rutledge, however, who brought this French trinket to my attention. (In French, the word “drague” is slang for flirt.)

Did it make it to North America? If you know anything of its fortunes over here, please tell us in the Comments section.

This letter from Richard Dyer appeared not in “Mandata” but rather in “Response,” the letters column of Mandate, in November 1983. Checking google, I find that Dyer has written extensively about Judy Garland. His earliest exploration of Judy and her vast gay audience seems to have appeared in Heavenly Bodies: Film Stars and Society, published in 1986. Wikipedia has an informative entry on Dyer, and you can read excerpts from his books online.

“I never will forget Jeanette MacDonald,” sang Judy Garland in a campy intro to the rousing anthem “San Francisco.”

“Just to think of her it gives my heart a pang,” Judy continued onstage at Carnegie Hall on April 23, 1961, a landmark event in show business and in pre-Stonewall gay pop culture. “I never will forget, how that brave Jeanette, just stood there in the ruins and sang….and saanng.”

On youtube, you can hear chuckles in the largely gay audience, but with only the briefest pause Judy bursts into “San Francisco, open your Golden Gate…..”

Twenty-one years later at Mandate, I’m opening the mail one morning when I come across the announcement of this elegiac event:

The name “Jeanette MacDonald” meant one thing to me then: camp of a fragrant and frou frou grade. It still does. I had seen one or two of her soprano epics costarring Nelson Eddy — Maytime, Bitter Sweet. Also Love Me Tonight, a 1932 picture that paired her with Maurice Chevalier — a lethal combination.

I recall associate editor Freeman Gunter’s guffaw when I read to him that line about the “Cryptside Presentation of Roses.” It sounded like something from The Loved One, a 1965 film that satirized the funeral business, with Liberace as a casket salesman who advises a coffin shopper that “rayon chafes, you know. Personally I find it quite abrasive.”

“We are running this in Mandata, aren’t we?” said Freeman.

When the December issue arrived, I sent a copy to Clara Roades, who had so thoughtfully mailed me the announcement. (I suspect she confused the title Mandate with something like Modern Maturity or Movie Life.) Her reply, a few weeks later, was a masterpiece of tactful befuddlement with a soupçon of shock. She was grateful to us for publicizing the fan club, even though….How I wish I had the letter in hand to reprint in its full-flavored entirety. Unfortunately, I can’t locate it.

I’m sad to report that Ms. Rhoades is no longer with us. These are the opening lines of her obituary at jeanettemacdonaldfanclub.com:

“August 15, 2011: Our beloved President of Jeanette’s Fan Club, The JMIFC, gave her sweet farewells and like Jeanette closed her eyes for eternal peace. In 1961, Jeanette hand-picked Clara to be the president of her fan club to carry on her legacy. We know Jeanette is so proud of her, for Clara did this to the last beat of her heart.”

I can’t help wondering whether Ms. Rhoades, and other fan club members, learned the Hollywood Babylonish details of Jeanette and Nelson Eddy…offscreen. If so, that copy of Mandate was perhaps not so startling after all. Not wishing to spread gossip, however, I refer you to Wikipedia for details.

If you’ve ever endured the pair singing “Ah, Sweet Mystery of Life” in Naughty Marietta (1935), you might guess that Mel Brooks knew their secrets when he had Madeleine Kahn sing a snatch of the Victor Herbert song while being pleasured by the Monster’s enormous Schwanzstucker in Young Frankenstein.

Speaking of fan clubs, I was a member of Susan Kohner’s. Like thousands of others, I was stunned and captivated by her performance in Imitation of Life, and also by that of Juanita Moore, the actress who played her mother. In the film, Susan is Sarah Jane Johnson, a young African American who passes for white owing to her light skin. She breaks her mother’s heart by denying who she really is. Her refusal even to acknowledge her mother leads to the mother’s heartbreak and eventual death, followed by a funeral that has melted even the hardest hearts since the film’s release in 1959.

Susan Kohner, Juanita Moore, and several others in the film were to enter my life in later years, although of course I had no inkling of this as a kid. Nor did I imagine in 1983, when I wrote this “Mandata” item for the November issue, that exactly twenty years later I would sit in Susan’s apartment in the East Sixties, just off Fifth Avenue, and say this to her while perusing her film-career scrapbooks: “You know, Susan, I’ve done a lot of research for my books, but this is the first time I’ve ever sat in the same room with a star I’m writing about.”

In one of those scrapbooks I came across this “Mandata” item.

A few years later, after many hours spent with Susan and with Juanita Moore, both of whom became my friends, St. Martin’s Press published my book: Born to Be Hurt: The Untold Story of Imitation of Life. It is dedicated “To Juanita Moore and Susan Kohner, with love and admiration.”

I often spoke by phone to Juanita, who lived in Los Angeles, and I always called on holidays. On December 25, 2013, she sounded less feisty than usual. She was close to one hundred at the time. Even so, I said, “Juanita, you’ll outlive us all.”

“God’s not ready for the old gal yet,” she replied. A week later, He was. Dear Juanita Moore died on January 31, 2013.

Susan — who uses her married name of Susan Weitz; she is the widow of fashion designer John Weitz — divides her time between New York and California. Her two sons, Paul Weitz and Christopher Weitz, are well known as producers, writers, and directors. Among the brothers’ many credits: American Pie (1999), which they co-directed.

Have you ever wondered what is meant by the term “subtle racism”? Almost any person of color can cite numerous examples. My late friend Juanita Moore endured a lifetime of racism, subtle and otherwise, but owing to her magnanimous spirit she retained her humanity and thus, in a sense, overcame.

I’m glad she was never aware of the example I’m going to cite here.

On February 12, 2009, a writer named Liz Brown reviewed Born to Be Hurt in the Los Angeles Times. The awkward, amateurish prose of her attack is a shocking example of book reviewer bias — and ignorance. Her ad hominem aspersions blame me for refusing “to engage the work of Rainer Werner Fassbinder, who had tremendous respect for [Imitation of Life director Douglas Sirk].” As if Fassbinder’s drug-addicted, goggle-eyed adulation of his betters required pages in my book devoted to his rhythmless, charmless product — the cinematic equivalent of poetic doggerel. I consider him the Ed Wood of German moviemaking.

Fassbinder, of course, is the darling of drab writers like Brown who hoist the banner of a certain kind of chickenshit liberalism — self-righteous, disdainful, hypocritical. Mistaking astringence for intellect, they’re the present-day equivalent of smug New England puritans without the theology.

Despite the absence of a Fassbinder tribute in my book, Liz Brown managed to “like knowing that Susan Kohner, who played the angry racially passing daughter in Imitation of Life, is the mother of Paul and Chris Weitz, the guys who made American Pie.” (“Directors” would have been a better word, but then Brown is no stylist.)

Along with interest in those “guys,” Brown liked knowing about all the white people in my book, no matter how fleeting their appearance: Lana Turner, John Gavin, John Stahl, Fannie Hurst, Jo Ann Greer, Karen Dicker, Sirk’s German ex-wife (a Nazi), his Jewish second wife Hilde Jary, Ann Robinson, John Waters, Lypsinka, Lex Barker. She even brings in David Thomson and his New Biographical Dictionary of Film, which is not mentioned in my 422 pages.

But who’s missing from Liz Brown’s review? Juanita Moore, the African American actress who, like her costar Susan Kohner, was nominated in 1959 for an Oscar as Best Supporting Actress. And whose life and career occupy a major portion of the narrative.

Nor does Brown’s review name any other African American person from the book. Not one. Omitted are Juanita’s friends and costars, all of whom, like her, struggled valiantly against Hollywood racism and the pervasive racism in the United States: Mahalia Jackson, Joel Fluellen (both of whom appear in Imitation of Life); and the African American stars of the 1934 Imitation of Life, Louise Beavers and Fredi Washington. Others in Brown’s racist omissions are Dorothy Dandridge, Robert Hooks, Sidney Poitier, Ruby Dee, Ossie Davis — friends and colleagues of Juanita Moore. And all in the book.

On the basis of her heinous omissions, I accuse Liz Brown not only of blatant racism but also of blatant stupidity! Not because she disliked the book, but because she skimmed it instead of reading.

Learning about the behind the scenes tidbits of movies, books, magazines, and art make for such an interesting read. Thanks for sharing your experiences. I always enjoy reading your articles.