Nostalgia is on the upswing, and no wonder. Any previous time looks better than the second coming of President Chickenshit. Even the Reagan Eighties seem marginally preferable; stupid fool that he was, Ronald Reagan at least was never hand-in-glove with Russia. He labeled the Soviet Union, as Russia then was, an “evil empire.” Putin has exponentially increased the Russian evil.

On April 2, 2024, my Substack post was Bonus Number 65, “Tales of Manhattan.” I opened with this paragraph:

Several readers have expressed a liking for those features in Did You Sleep With the Models? that take them back to the New York, meaning the Manhattan, of the 1980s. The early days of that decade were pure bliss; I wrote about them in Chapter Two. All too soon, however, the shadow of AIDS eclipsed the carefree days and orgasmic nights, those delirious hours we imagined lasting on and on.

Even so, those of us who experienced New York in that decade can summon up events that would not have taken place elsewhere. In this post I’ll focus on movies. In subsequent ones, I’ll talk about New York theatre, Broadway and off-Broadway, as well as memorable theatre way off.

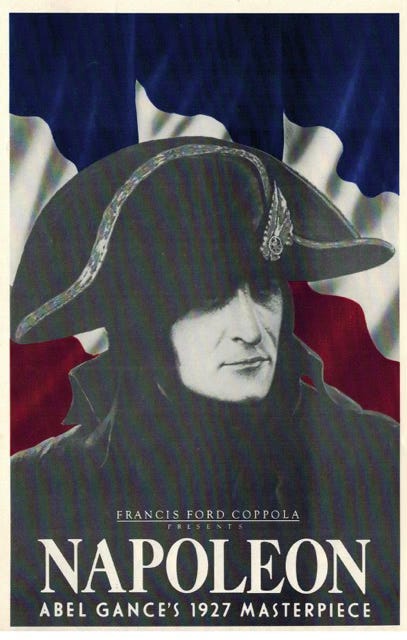

One of the biggest cinematic happenings of the decade took place at Radio City Music Hall on several evenings in late January and early February 1981. Le tout New York turned out for the four-hour restored version of the 1927 silent film Napoléon by French director Abel Gance.

The meticulous restoration was carried out by British film historian Kevin Brownlow. Francis Ford Coppola, then at the top of his form as director-auteur, financed the presentation. His father, Carmine Coppola, composed a new score for the film

and conducted the American Symphony Orchestra. The cavernous Music Hall accommodated the required three screens for the film: the final eighteen minutes, filmed by three cameras in a process called Polyvision, played on three screens as viewers watched simultaneously what amounted to three separate films side by side.

The director, Abel Gance, was ninety-one years old at the time. Owing to ill health, he was unable to fly from his home in France to attend the screening. (He died later that year.) His phototograph and his comments from the film’s 1927 premiere appeared in the Music Hall program:

On the back cover of that program was a photograph of Gance meeting D.W. Griffith, the great American film pioneer whose influence on world cinema is incalculable.

Not every evening at the movies was such a grand experience. Apart from the Ziegfeld Theatre on West Fifty-fourth Street and a few others, you were likely to encounter typical New York annoyances. Projectionists tended either to fall asleep in their booth or to pay scant attention, meaning that the film would stop or slide out of focus. An outcry would erupt from the audience: “Focus!” “Fix the fuckin’ frame!” “Wake up, asshole!”

Watching Fred Schepisi’s 1984 Iceman in a theatre on Third Avenue, I noticed a dainty mouse at my feet. Unsure whether he was more interested in nibbling popcorn that littered the floor or in running up my leg, I changed seats. He followed. I considered suggesting to management that they hire a resident cat.

At the Ziegfeld, of course, the frame never came unfixed and no mouse would dare interfere with cinephiles. That’s where you saw big-deal, first-run productions (they were looked on as films, not movies) such as Close Encounters of the Third Kind and Apocalypse Now.

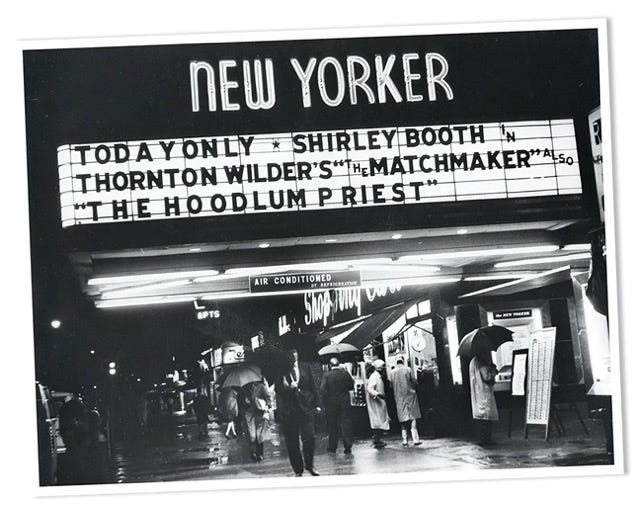

Elsewhere, in huge Times Square movie barns for instance, the heat was often inadequate in winter, and one frigid Saturday afternoon at the New Yorker Theatre, Broadway and Eighty-eighth Street, the heat flickered out entirely. This was in the late ‘70s, the picture was Mr. Klein, a bad film by hit-or-miss director Joseph Losey, and it starred Alain Delon and Jeanne Moreau. Why didn’t I leave and demand my money back? Because, like thousands of others, I was a movie addict. I saw between 150 and 200 pictures a year.

And in summer I endured the stuffy air of sluggish air conditioning to feed my addiction.

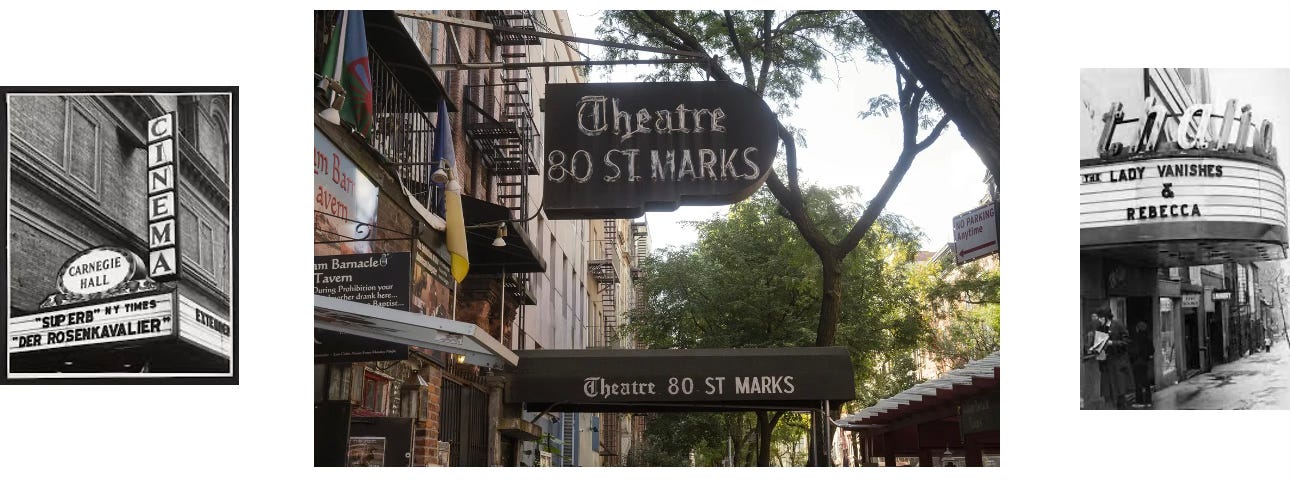

Out of those movie hundreds that I saw, perhaps twenty or thirty were new releases. The rest were older movies screened in revival houses, the best known of which were Theatre 80 St. Marks in the East Village, the Elgin in Chelsea, the Film Forum in the West Village, the Carnegie Hall Cinema in Midtown, and the Thalia on the Upper West Side.

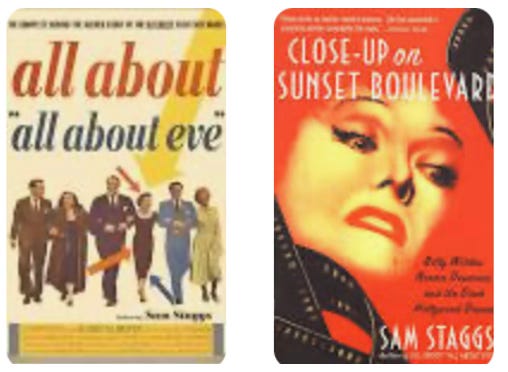

These buildings dated from the 19th and early 20th centuries. The theatres were generally well managed by actual movie lovers who took pride in the vintage pictures they screened and who insured comfort for their devoted audiences. The Elgin is where I first saw, on a double bill, All About Eve and Sunset Boulevard — never dreaming that a couple of decades later I would write a book about the making of each one.

It was in these revival houses that I came to grasp the panorama of film history. I had gone to the movies with my parents from early childhood, later on my own or with high school and college friends. Not until the mid-1960s, however, were Hollywood movies taken seriously as an art form by more than the cognoscenti.

Pauline Kael, writing her weekly movie reviews in The New Yorker, was to a great extent responsible for the intense new interest in movies, especially among the young. I met her through a mutual friend in 1971, even before I moved to New York. In the ‘80s, as editor-in-chief of Mandate, Honcho, and Playguy, I often attended the same screenings as Pauline. On several occasions I accompanied her to a late movie in Times Square, even after a murder took place there…at a late night movie.

“Is that a gun in your purse?” I said.

“Oh sweetie,” she purred, “the hoodlums won’t bother us. I’m the one on deadline.”

If that murder took place because some chatterbox wouldn’t shut up, I applaud the perpetrator. In the mid-seventies, when I arrived in New York, audiences paid close attention. Gradually, however, they came to consider theatres as extensions of their living rooms. It became necessary, and usual, to turn around and “Shush!” Sometimes it worked, other times not. At the Regency on the Upper West Side I once had the misfortune to sit near two old dames who might as well have been luncheoning at Schrafft’s. A shush didn’t work. Then I turned to glare. They were oblivious. Finally I said aloud, “Please be quiet! Please.”

The response: “Oh, we didn’t know anyone was listening.”

Such audience misbehavior is different from Los Angeles, at least in my experience. Audiences there are as reverent as if they were in church. Many of those watching the screen are no doubt involved to some extent in film production.

Then, too, special event screenings are common in Los Angeles, and they are prized by everyone involved. In 1999, when I was working on the Sunset Boulevard book, I attended one such with Nancy Olson, who appeared in the film, and her husband, Alan Livingston. While the three of us chatted in the lobby before show time, I heard a familiar voice call out, “Nancy! Alan! I thought you’d be here.” It was Jane Withers. I asked for her phone number and later interviewed her for my next book. In case you haven’t read Born to Be Hurt: The Untold Story of Imitation of Life, here’s what she told me.

“One night my phone rang at one o’clock in the morning. It was Rock Hudson. He said, “Were you in Imitation of Life?” (He meant the 1934 version, not the 1959 remake.) “I’ve got a thousand-dollar bet here that it’s you.” Withers laughed as she told me the

story. “ ‘Good gravy, ’ ” I said, ‘that’s a lot of money just to find out whether that was me or not.’ But Rock won his bet. Yes, I was in that schoolroom scene where Louise Beavers brings a raincoat and galoshes to her little daughter. I was on the set for one day, as an extra, and I got paid five dollars.”

This bonus installment was a most enjoyable read. Filled with genuine nostalgia for a real time and place, not the lifeless, bland recall that sometimes passes for or is misconstrued as nostalgic. The words of Abel Gance from the Napoleon program was an added treat, as was the photo of the young director with D.W. Griffith.

Gance’s love of the art form made so very clear by his statement: “cinema is the climax of life.”