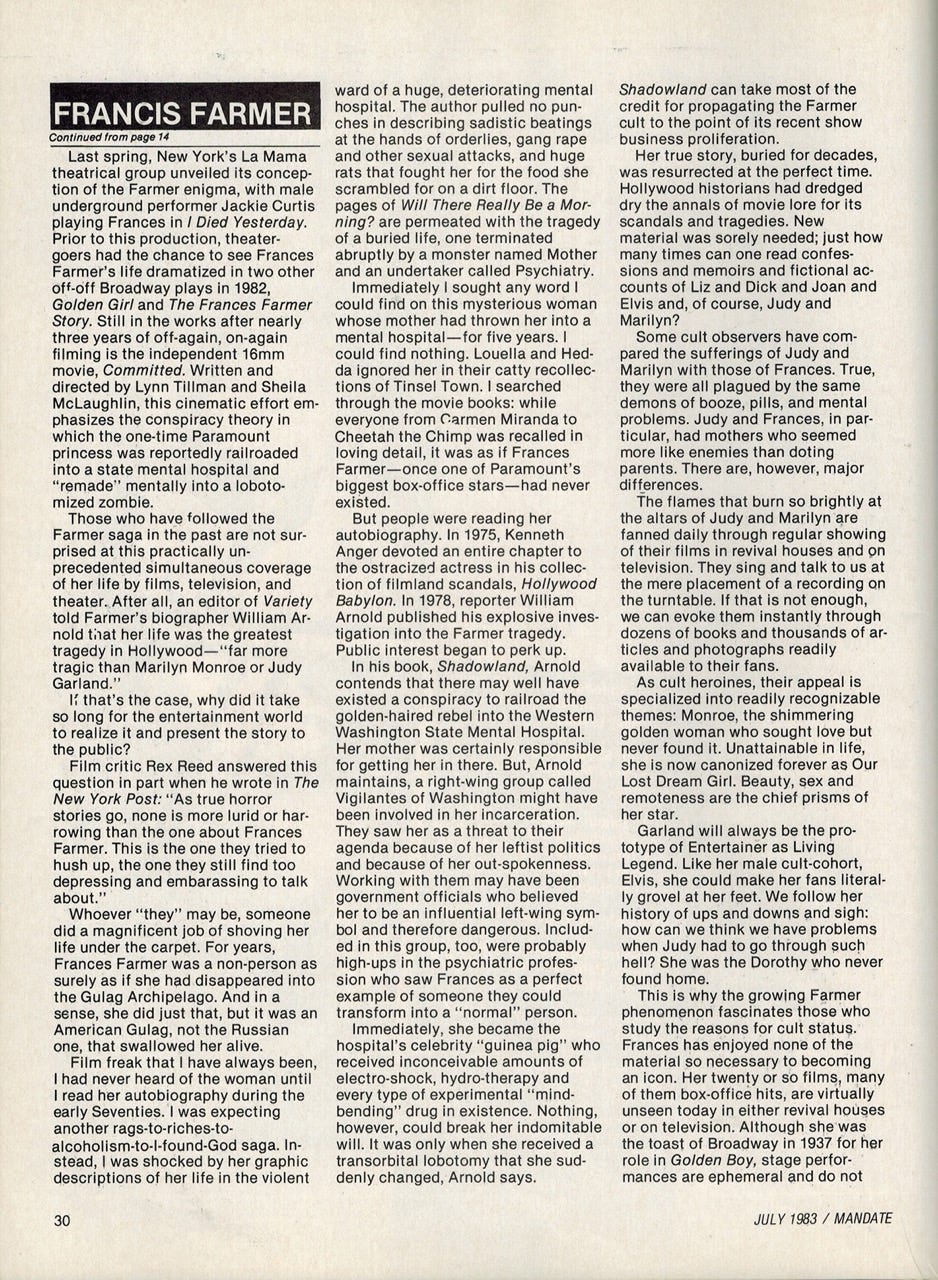

The case histories of Judy Garland and Marilyn Monroe seem straightforward compared to that of Frances Farmer (1913-1970). For almost every fact related to her off-screen life, there is a contradiction. Surely the greatest dispute is this: did she or did she not undergo a forced transorbital lobotomy during her brutal confinement in a mental hospital in the 1940s?

Jery Tillotson’s article, which ran in the July 1983 issue of Mandate, is an introduction to the life and work of this enigmatic actress. I’ve been fascinated by her story since childhood, when I happened to see her appearance on the grotesque television show This Is You Life. Not long after that, the fan magazines ran a few features on her — almost certainly full of lies — and she was off my radar until her death in 1970 and her posthumous autobiography, Will There Really Be a Morning?, which was published a year later.

That haunting title comes from a poem by Emily Dickinson, whose placid external life as a New England spinster concealed emotional storms and torments to equal those of Frances Farmer…or so we speculate, reading her letters and her 1,775 poems, give or take a few. If you don’t know Dickinson’s poem already, here it is:

Will there really be a “Morning”?

Is there such a thing as “Day”?

Could I see it from the mountains

If I were as tall as they?

Has it feet like Water lillies?

Has it feathers like a Bird?

Is it brought from famous countries

Of which I have never heard?

Oh some Scholar! Oh some Sailor!

Oh some Wise Man from the skies!

Please to tell a little Pilgrim

Where the place called “Morning” lies!

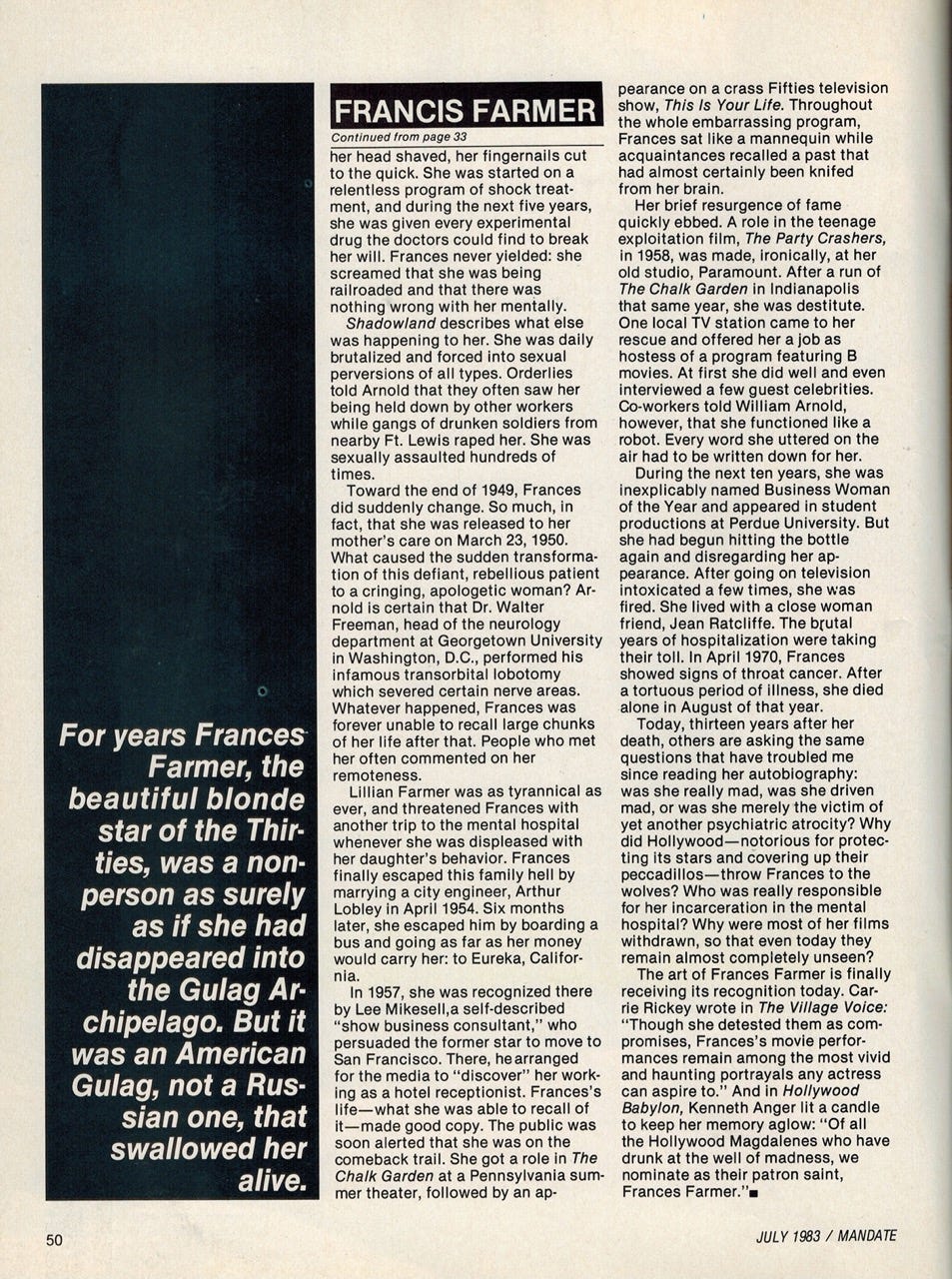

The dark night out of which Dickinson wrote is subdued, peculiar but under control. Besides her pain, she found joy in nature, in books, and in a small circle of friends. Frances Farmer’s life, by contrast, from the early 1940s until 1950, was unrelenting midnight. She was destroyed not only by Hollywood but also by the virulent psychiatric establishment. For her, morning never came.

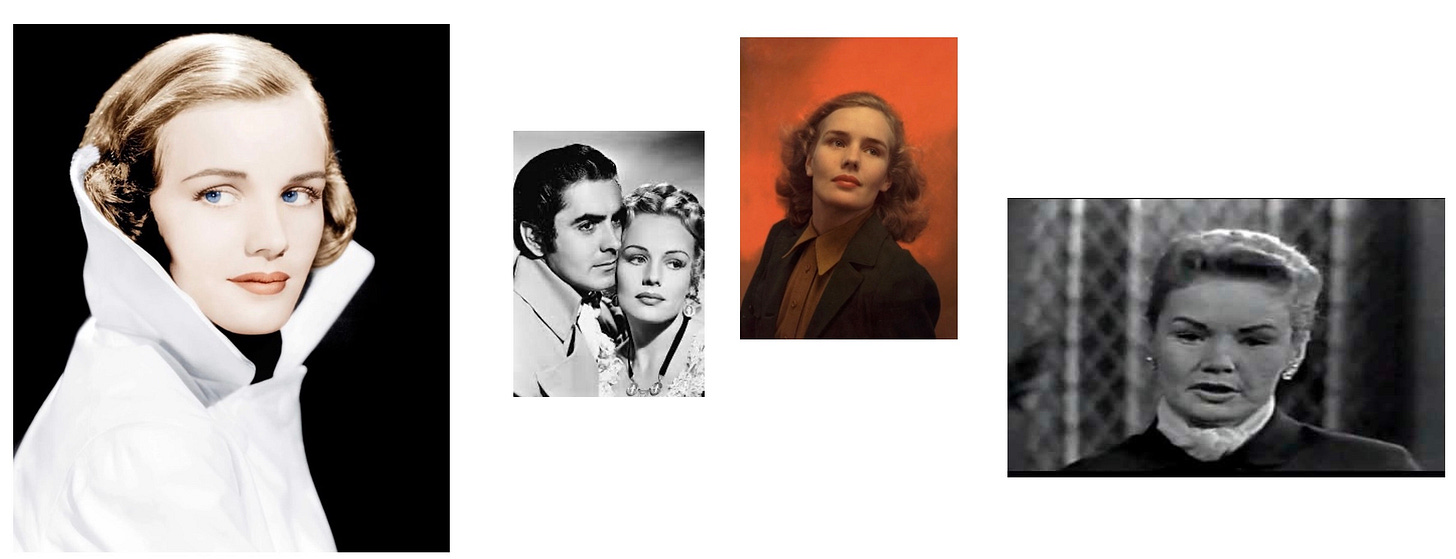

Before I turn the program over to Jery Tillotson, I’ll say a word about This Is Your Life, which I recently revisited on youtube. The smarmy host, Ralph Edwards, suggests a child molester who has found God. Poor Frances, who consented to appear on the show, does indeed seem lobotomized. A big chunk of her is missing.

If you knew her life only from this macabre piece of work, you might think she had “a drinking problem,” and some turbulent days before she turned to religion. Her college drama professor makes a cheery little speech on the show; so does a high school teacher. Frances, by all accounts a pyrotechnic woman who might or might not have been mentally ill, by this sad point is like a guttering candle on the verge of extinction.

Jessica Lange, who starred in the biopic Frances (1982), made this cogent observation about This Is Your Life: “Of all the great tragedies in Frances’s life, I think that was probably one of the worst — her appearance on that program!”

If you’re unsure why 1950s televison was called, in 1961 by the chairman of the FCC, “a vast wasteland,” watch This Is Your Life. It should come with a trigger warning. Among the comments that follow the Frances Farmer segment on youtube: “This isn’t an interview. It’s a crucifixion.” And another: “Francis lived across the street from me in Indianapolis. I liked her very much, because her love of animals led her to receive a lost cat I'd found at a roadstop. She was kind and gracious.”

A ghastly beau geste at the end of the show: Ralph Edwards presents Frances with a new car for her comeback, so that she can drive to “the many interviews” in Hollywood that he predicts, without a shred of evidence, are waiting for her. The comeback doesn’t happen. She makes one B movie, The Party Crashers (1958), and a few TV appearances.

That car, like so much in Frances Farmer’s life, was a curse, like a free ticket on the Titanic. Why? It was an Edsel, the greatest flop in American automobile history!

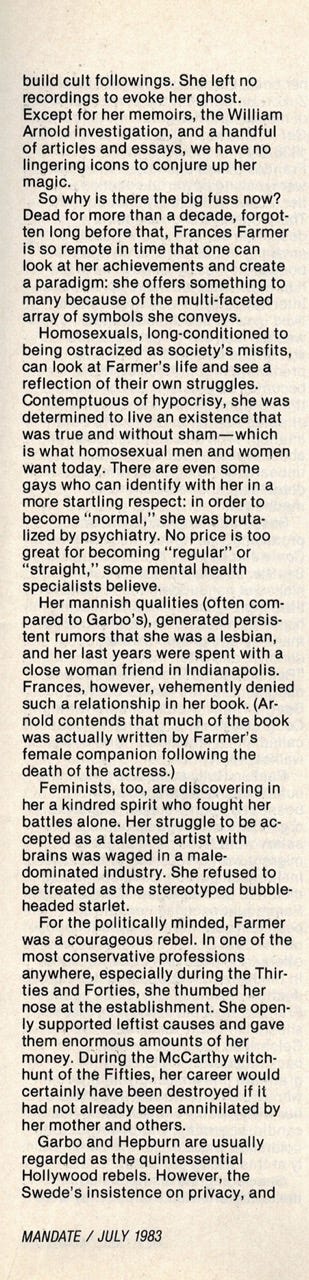

In that same issue of Mandate, associate editor George De Stefano wrote an appreciation of Jessica Lange, who, as he points out, bears “a startling resemblance” to Frances Farmer. It’s hard to believe, looking back, that Frances was only Lange’s sixth film. She has long been an established star, with several dozen pictures to her credit as well as TV movies, Broadway, and this year even a podcast.

I found Frances far from pleasing when I saw it in 1983. Watching it again recently, I thought it terrible except for two performances: Lange’s, and Kim Stanley’s as Frances Farmer’s hellish mother. If the producer, director, and casting director had gone looking for the worst available actors, they couldn’t have done worse than Sam Shepard. Every line he speaks here, and in his string of undistinguished performances over the years, sounds like every other line he spoke in every other movie. He was also a playwright whose plays are as drab as his acting.

Jordan Charney, playing Harold Clurman, seems not to have been informed that Clurman was not only a founding member of the Group Theatre but one of this country’s best directors and theatre critics. This terrible performance, like so many others in the picture, is no doubt the fault of Graeme Clifford, the director. Ironically, Clifford was a film editor before he became a director. You would never guess it from the way Frances is flung together: an unstable, ragtag jumble of shots and sequences that lumbers on for over two hours in search of a film. The editor of Frances was John Wright, who no doubt shares guilt with Clifford for the shambles. Scenes don’t really look like scenes; they lack center, point of view, basic shape. There’s endless conflict, but the conflicts resemble random street brawls more than scenes rehearsed, and performed, by actors.

Jeffrey DeMunn as Clifford Odets brings a gnawing-rodent quality to his performance. Audience members unfamiliar with Odets, Clurman, and with actors-as-serfs in medieval Hollywood, are no doubt puzzled by the slapdash relationships that help to doom Frances. But very little is made clear by script or direction.

The best things in the picture are set decorations and antique cars. These look fine owing to the cinematography of masterful László Kovács. If he had directed Frances, it might have been one of the better movies of the 80s and not one of the worst.