I am sad to announce the death of Charles Harmon Cagle, the author of today’s feature from Mandate.

Charles, a frequent contributor, specialized in biographical essays on famous gay and bisexual men of the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. His first one appeared in the issue of December 1982. I have included several of his articles in Did You Sleep With the Models?, with more to come in future.

I knew Charles during the Mandate years only through letters and manuscript submissions, all of which I eagerly accepted. Why didn’t we speak by phone? Probably because I was always short of time, and so was he as professor of creative writing at Pittsburg State University in Kansas, where he taught from 1960 until retirement in 2000. In an early letter he mentioned his teaching career, and I remember wondering about possible repercussions in a conservative state.

When I began writing this memoir in 2020, two years before I discovered Substack, I wanted Charles’s update. But how to find him? There was his address online; my letter began, “First of all, I hope I’ve reached the right Mr. Cagle. Are you the one who contributed to Mandate back in the 1980s when I was editor-in-chief?”

A week later, a reply from Charles. I had reached the right Mr. Cagle.

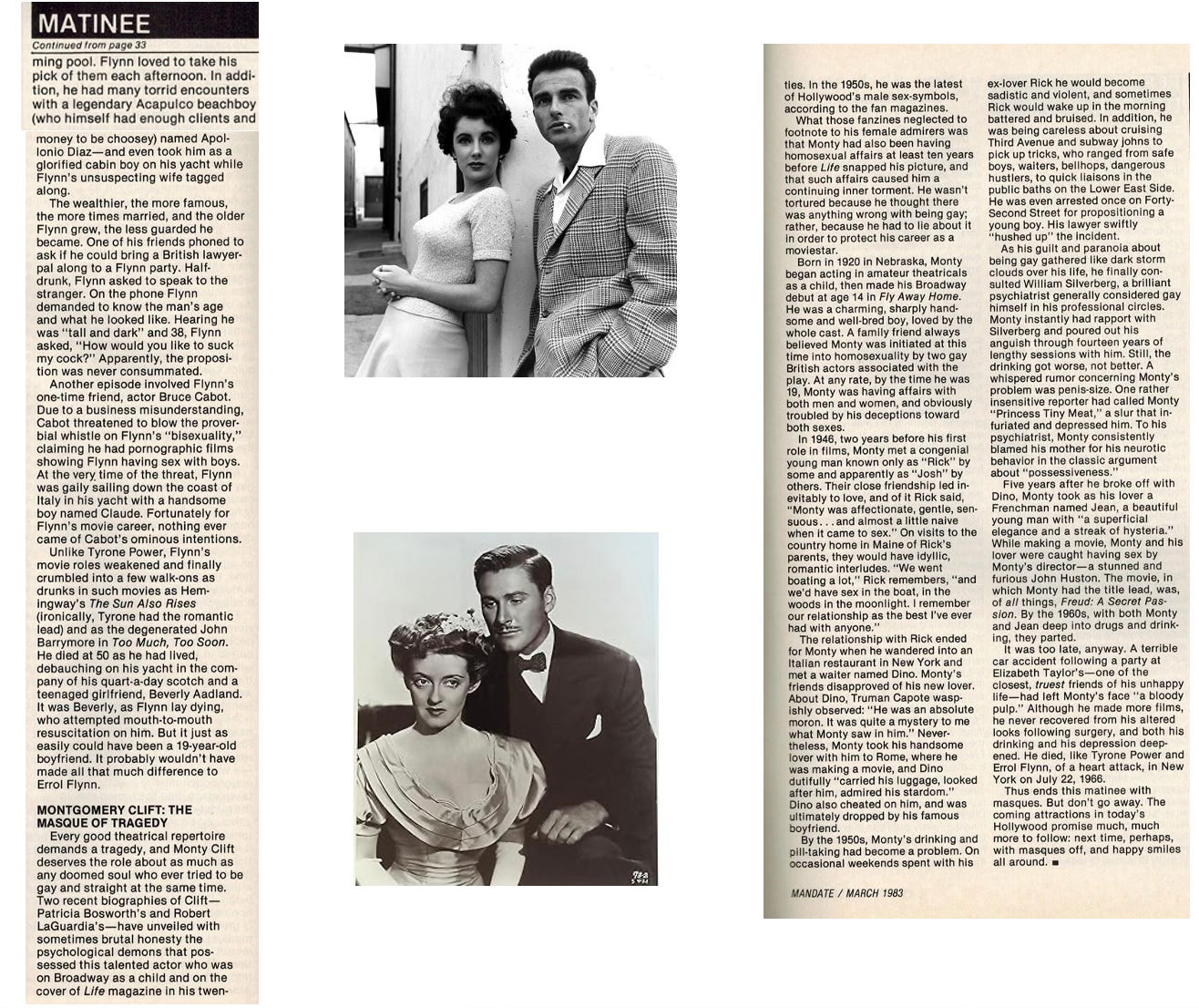

After expressing surprise at hearing from me, he continued, “Between 1982-85 I wrote sixteen articles for Mandate. The subjects were, in no particular order, Cocteau, Gide, Tchaikovsky, Tyrone Power/Errol Flynn/ Montgomery Clift, De Sade, Proust, D.H. Lawrence, Verlaine and Rimbaud, W.H. Auden and Chester Kallman, Henry James, E.M. Forster, Hemingway and Homosexuality, Whitman, Thoreau, Edward Carpenter, and Homosexuality in Germany.”

He added: “I also published two articles in Blueboy, but the bastards never paid me. You did at Mandate. I still have all your letters to me. I often thought about a book of my collected articles, plus some extra ones I never wrote — such as Oscar Wilde’s dalliance with boys after he got out of prison — but too late now since I will be ninety in September.”

In subsequent emails, I learned so much about his career prior to Mandate that I realized Charles himself would have qualified as an excellent subject for a bio feature. Between 1967 and 1973 he wrote and sold some sixty paperback novels for such publishers of adult pulp as Greenleaf Classics, Bee-Line Books, and Neva Paperbacks. “I often produced two-and-a-half books a month,” he said, “writing one chapter daily and four chapters on a weekend while teaching full time. My forte was plotting, and what one editor called my ‘sardonic humor’ and my attention to the markets.

“Only about eight of these novels were gay because of market demands. These bore such titles as A Queen’s Fury, The Price of Pansies, and Mr. Fancy Panties. I had sixteen pen names. I only stopped writing these novels when the market faded. That’s when I turned my attention toward Mandate, which gave me a reason to attach my real name to something worthwhile.

“In time it became known among the faculty that I was gay and a writer of ‘dirty books.’ Several colleagues in the English Department were delighted by my articles on literary figures, and copies of Mandate were quietly passed around. The chairman of the Foreign Language Department — French, gay, and a good friend — was thrilled to see my André Gide article in print, especially since his dissertation at the Sorbonne was on Gide. My best friend, curator of special collections in the university library, was interested in my Walt Whitman article since he owned a holograph Whitman manuscript; after his death, it sold for thousands of dollars. This same friend used to say I should write a book called Porn in the Corn: Confessions of a Kansas Pornographer.”

Charles also wrote a television play, The Sudden Truth, which aired in 1957 on NBC’s afternoon drama series Matinee Theatre. The plot, as he described it: a widow travels from Texas to France ten years after her son was killed in World War II in search of the last man to see him alive.

Charles also wrote a number of plays for local groups such as the Barn Players in Kansas City and for college performers.

As for those repercussions I wondered about: Only once did Charles have to defend himself because of his off-campus career. “A Bible-thumping harpy, the mother of a female freshman student, got wind of the fact that a degenerate writer of obscene books was teaching her daughter how to use the semicolon. She marched into the university president’s office and demanded that something be done about me.”

The dean was called onto the case, along with the chairman of the English Department. The administration and faculty at Pittsburg State U. must have been enlightened and tolerant, certainly compared with today’s schools where refusal to conform to any outlandish student whim can result in censure and even dismissal. After a few pro forma meetings, the controversy simmered down and — “the innocent daughter remained in my class.” One wonders whether she mastered the semicolon; or even the full stop.

.